San Lazzaro degli Armeni

San Lazzaro from a bird's-eye view and as seen from a boat | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°24′43″N 12°21′41″E / 45.411979°N 12.361422°E |

| Adjacent to | Venetian Lagoon, Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean Sea |

| Area | 3 ha (7.4 acres) |

| Administration | |

| Region | Veneto |

| Province | Province of Venice |

| Commune | Venice |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 17 (2015)[1] |

| Ethnic groups | Armenians |

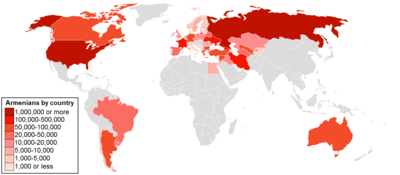

San Lazzaro degli Armeni (Italian: [san ˈladdzaro deʎʎ arˈmɛːni], lit. "Saint Lazarus of the Armenians"; sometimes called Saint Lazarus Island in English; Armenian: Սուրբ Ղազար, romanized: Surb Ghazar) is a small island in the Venetian Lagoon which has been home to the monastery of the Mekhitarists, an Armenian Catholic congregation, since 1717. It is one of the two primary centers of the congregation, along with the monastery in Vienna.[2]

The islet lies 2 km (1.2 mi) to the southeast of Venice proper and west of the Lido and covers an area of 3 hectares (7.4 acres). Settled in the 9th century, it was a leper colony during the Middle Ages, but fell into disuse by the early 18th century. In 1717 San Lazzaro was ceded by the Republic of Venice to Mkhitar Sebastatsi, an Armenian Catholic monk, who established a monastery with his followers. It has since been the headquarters of the Mekhitarists and, as such, one of the world's prominent centers of Armenian culture and Armenian studies. Numerous important publications, such as the first complete dictionary of the Armenian language (1749–69) and the first modern history of Armenia (1781–86), were made in the island by the monks which made it an early major center of Armenian printing.

San Lazzaro has been enlarged nearly four times from its original size through land reclamation. It was recognized as an academy by Napoleon in 1810 when nearly all monasteries of Venice were abolished. A significant episode in its history is Lord Byron's visit in 1816–17. The island is one of the best known historic sites of the Armenian diaspora. The monastery has a large collection of books, journals, artifacts, and the third largest collection of Armenian manuscripts (more than 3,000). Over the centuries, dozens of artists, writers, political and religious leaders have visited the island. It has since become a tourist destination.

Overview

[edit]

San Lazzaro lies 2 km (1.2 mi) to the southeast of Venice proper and west of the Lido.[3] The islet is rectangular-shaped[4] and covers an area of 3 hectares (7.4 acres).[5][6][7] The island is accessible by a vaporetto from the San Zaccaria station (Pier B1) with guided tours in multiple languages available.[5][8] Some 40,000 people visit the island annually,[9][1] with Italians making up the majority of visitors.[10]

The island's Italian name, San Lazzaro degli Armeni, literally translates to "Saint Lazarus of the Armenians".[5][11][12] It is often referred to in English as Saint Lazarus Island.[5] In Armenian, it is called Surb Ghazar[a] (Սուրբ Ղազար), meaning "Saint Lazarus".[13][4]

Population

[edit]The number of monks, students, and other residents at San Lazzaro has fluctuated throughout history. Twelve monks led by Mkhitar Sebastatsi arrived in Venice in 1715.[14] A century later, in 1816, when Byron visited the island, there were some 70 Mekhitarists in San Lazzaro.[5] Their number has been smaller thereafter. By the early 1840s, the island housed 50 monks and students.[15] By 1960, some 20 resident monks were reported.[16] A Los Angeles Times writer noted in 1998 that San Lazzaro is still a "monastic hub of activity," although at the time the monastery housed only 10 seminarians and 10 fathers.[17] Teresa Levonian Cole wrote in 2015 that 12 vardapets (educated monks) and five novices reside in San Lazzaro.[10]

History

[edit]

Middle Ages

[edit]The recorded history of the island begins in the 9th century. In 810, the Republic of Venice allocated the island to the abbot of the Benedictine Monastery of St. Ilario of Fusina.[7] Leone Paolini, a local nobleman, obtained the island as a gift from the Abbot Uberto di Sant'Ilario and built a church, initially dedicated to Pope Leo I. It soon became an asylum for those infected with leprosy.[3] In the 12th century, leprosy had appeared in Venice as a result of trade with the East. Paolini transferred the simple hospital of San Trovaso to the island.[7] Thus, a leper colony was established at the island, which was chosen for that purpose due to its relative distance from the principal islands forming the city of Venice. It received its name from St. Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers.[18][5] The church of San Lazzaro was founded in 1348, which is attested by an inscription in Gothic script. In the same year, the hospital was renovated and its ownership transferred from the Benedictines to the patriarchal cathedral of San Pietro. Leprosy declined by the mid-1500s and the island was abandoned by 1601 when only the chaplain and some gardeners remained at the island to grow vegetables. In the second half of the 17th century the island was leased to various religious groups. In 1651 a Dominican order settled at the island after fleeing from Turkish-occupied Crete. Jesuits also briefly settled there.[7] By the early 18th century only a few crumbling ruins remained.[18]

Armenian period

[edit]

Establishment

[edit]In April 1715, a group of twelve Armenian Catholic monks led by Mkhitar Sebastatsi (English: Mekhitar of Sebaste, Italian: Mechitar) arrived in Venice from Morea (the Peloponnese), following its invasion by the Ottoman Empire.[14] The monks were members of a Catholic order founded by Mkhitar in 1701, in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire.[4] The order moved to Modone (Methoni), on the southern shore of the Peloponnese, in 1703,[20] after repressions by the Ottoman government and the Armenian Apostolic Church. In 1712 the order received recognition by Pope Clement XI.[21] Victor Langlois wrote that a Venetian admiral and the Venetian governor of Morea, "sympathizing deeply with the fearful distress of the unfortunate community, yielded to their earnest entreaties for permission to embark on a government vessel which was about to leave for Venice."[20]

On September 8, 1717, on the Feast of the Nativity of Mary, the Venetian Senate ceded San Lazzaro to Mkhitar and his companions, who agreed not to rename the island.[22][23] He was reminded of the monastery on the island of Lake Sevan, where he had sought education earlier in his life.[24] Upon acquisition, the monks began works of restoration of existing buildings on the island.[23] The entire community then relocated to the island in April 1718 when the buildings on San Lazzaro became habitable. Mkhitar himself designed the plan of the monastery, which was completed by 1840.[25] The monastery originally included 16 cells for monks, which were adjusted from the old hospital. The church's restoration lasted from May to November 1722. Mkhitar died in 1749.[26] The bell tower was completed a year later, in 1750.[7]

Later history

[edit]

The Venetian Republic was disestablished by Napoleon in 1797. In 1810, he abolished all monastic orders of Venice and the Kingdom of Italy, except that of the Mekhitarists in San Lazzaro.[28][15] The Mekhitarist congregation was left in peace, according to some sources, due to the intercession of Roustam Raza, Napoleon's Mamluk bodyguard of Armenian origin.[29][30] Napoleon signed a decree, dated August 27, 1810, which declared that the congregation may continue to exist as an academy.[31][32] Since then, San Lazzaro has also been known as an academy, and sometimes referred to in Latin as Academia Armena Sancti Lazari.[33]

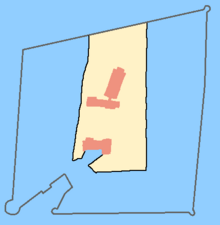

The monastery has been enlarged significantly through land reclamation four times since the 19th century. First, in 1815, the Mekhitarists were permitted by Austrian Emperor Francis II to expand the island. The area north of the island was filled which doubled its area from 7,900 m2 to 13,700 m2. In 1836, a boundary wall around the island's newly reclaimed area was built. The channel of the boathouse was filled in 1912 and it was moved to the far western corner. The shoreline was straightened. These adjustments increased its area to 16,970 m2. San Lazzaro's latest major enlargement occurred in post-World War II period. Between 1947 and 1949, the island was expanded on the southeast and the southwest. The island now has an area of 30,000 m2 or 3 hectares.[3][7][6]

- Gradual expansion of San Lazzaro

-

The island when Armenian monks arrived, 1717

-

The construction of the monastic complex by Mkhitar (1740) and the printing house (1789)

-

The enlargement on the northern side of the island (1818) and the wing of the new printing house (1823–25)

-

Enlargement of the southern side of the island (1947–49)

20th century and beyond

[edit]

The island was heavily affected by the unprecedented acqua alta of November 4, 1966. The flooded sea water entered the main church and flooded the enclosed garden for around 12 hours. The library and the manuscript depository were not affected by the flood and none of the churchmen suffered injuries.[34] A fire broke out on the night of December 8, 1975, which partially destroyed the library and damaged the southern side of the church, and destroyed two Gaspare Diziani paintings.[7]

Between 2002 and 2004, an extensive restoration of the monastery's structures was carried out by the Magistrato alle acque under the coordination of Consorzio Venezia Nuova, an agency of the Italian Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport. It included restoration of the island's shores and its walls and the boathouse.[7]

San Lazzaro hosted the pavilion of Armenia during the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015.[35] The exhibition, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide and curated by Adelina Cüberyan von Furstenberg, won the Golden Lion award in the national participation category.[36][37]

San Lazzaro was affected by the November 13, 2019 flood, the heaviest since 1966.[38][39][40]

Monastery

[edit]

San Lazzaro is entirely occupied by the Mekhitarist monastery of San Lazzaro, which is the headquarters of the Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Congregation. The monastery is known in Armenian as Մխիթարեան Մայրավանք, M(ə)khitarian Mayravank', which literally translates to the "Mekhitarist Mother Monastery" and in Italian as Monastero Mechitarista.[41] The monastery currently contains a church with a bell tower, residential quarters, library, museums, picture gallery, manuscript repository, printing plant, sundry teaching and research facilities, gardens,[4] a bronze statue of Mkhitar erected by Antonio Baggio in 1962,[7] an Armenian genocide memorial erected in the 1960s,[42] and a 14th-century basalt khachkar (cross stone) donated by the Soviet Armenian government in 1987.[7]

The cloister of the monastery consists of a colonnade of 42 columns in the Doric order. There is a 15th-century water well in the center of the cloister, which is surrounded by trees and shrubs. A Phoenician and early Christian inscriptions, a first century headless statue of a Roman noble from Aquileia and other artifacts were found there.[7]

The bell tower with an onion dome was completed in 1750.[4] It is not attached to the church and stands alone near the northern side of the church.[7]

The church

[edit]

The church of San Lazzaro, although renovated several times through centuries, retains the 14th century pointed arch style. The church was restored extensively by Mkhitar in 1722, five years after the settlement of Armenian monks. He completely rebuilt the altar. Its apse was extended in 1899 primarily with an addition of neo-Gothic elements.[7] The church has a neo-Gothic interior.[4] It is three-naved, supported by 6 red marble columns.[7] The main altar is in Baroque style. The three main windows of the altar's apse have stained glass which depict from left to right: Sahak Patriarch, Saint Lazarus, and Mesrop Mashtots. In the church, there are frescoes and paintings by Antonio Ermolao Paoletti depicting Saint Peter, Saint Paul, John the Baptist and Saint Stephen. The tomb of Mkhitar is located in the front of the altar.[7]

Besides the main altar, there are four other altars dedicated to the Holy Cross, St. Gregory the Illuminator, Mary, and Anthony the Great. All built in the period of 1735–38 by Mkhitar. They are all adorned by pieces of works, mainly by Venetian artists. The St. Gregory altarpiece by Noè Bordignon depicts the saint performing the baptism of the Armenian king Tiridates III. The altarpiece dedicated to the mother of Jesus depicts the Nativity of Mary by Domenico Maggiotto. The altarpiece of St. Anthony by Francesco Zugno depicts the founder of the Oriental monasticism who inspired Mkhitar.[7]

- Paintings

Within the church, there are paintings of Armenian saints by Paoletti created in 1901: Ghevond, Hripsime, Nerses of Lambron, Nerses the Great, Sandukht, Vardan, Gregory of Narek, Nerses Shnorhali. Other significant paintings include Madonna with Child by Palma il Giovane (Jacopo Negretti), the baptism of king Tiridates III by St. Gregory the Illuminator by Hovhannes Patkerahan (1720), Assumption of Mary by Jacopo Bassano, Annunciation and Mother of Mercy by Matteo Cesa, the Flood by Leandro Bassano, Flight into Egypt by Marco Basaiti, Annunciation by Bernardo Strozzi, St. Thecla and Sts. Peter and Paul by Girolamo da Santacroce, Moses Saved from the Waters and Archangel Raphael by Luca Carlevarijs.[7]

Gardens

[edit]The gardens of the monastery have been admired by many visitors.[43][44][45][46] "The island ... with its flower and fruit gardens, is so well kept that an excursion to San Lazzaro is a favourite one with all visitors to Venice," noted one visitor in 1905.[47] Irish botanist Edith Blake wrote: "The garden in the centre of the cloisters was gay with flowers, and there was a calm, peaceful air of repose over the whole place."[48]

The monks at San Lazzaro make jam from the roses grown in the gardens. The jam, called Vartanush,[49][50][b] is made from rose petal around May, when the roses are in full bloom. Besides rose petal, it contains white caster sugar, water, and lemon juice.[51] Around five thousand jars of jam are made and sold in the gift shop in the island. Monks also eat it for breakfast.[52]

Collections

[edit]Library

[edit]

The library contains 150,000 to 200,000[c] printed books in Armenian, as well as European and Oriental languages. Some 30,000 European books printed before 1800 are kept at the library.[1] The entire collection includes books on the arts, the sciences, history, natural history, diverse classical texts, literary criticism, major encyclopedias and other reference books.[7]

The floor of the library is decorated in a Venetian style. Its ceiling, partially destroyed in the 1975 fire, was painted by Francesco Zugno and depicts Catherine of Alexandria, the four fathers of the Latin Church (Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, St. Gregory the Great), and fathers of the Armenian Church. A chalk sculpture of Napoleon II by Antonio Canova is preserved in a glass cabinet in the library. A sculpture of Pope Gregory XVI by Giuseppe De Fabris, presented to the Mekhitarists by the Pope himself, is also kept at the room.[7][16]

In 2021 the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative donated $50,000 to support the library in memory of Vartan Gregorian.[56]

Manuscripts

[edit]

The Mekhitarists regard the collection of manuscripts the greatest treasure of San Lazzaro. During the 19th century, Mekhitarist monks extracted from these manuscripts and published some previously unpublished pieces of Armenian and non-Armenian literature.[7] According to the magazine of the Church of England, by 1870, San Lazzaro had the second largest collection of Armenian manuscripts after Etchmiadzin having some 1,200 manuscripts in possession.[29] The exact current number of manuscripts preserved at San Lazzaro is unknown. According to Bernard Coulie the number is around 3,000,[57] which comprises some 10% of all extant Armenian manuscripts.[58] According to the Mekhitarist Congregation website the monastery contains 4,500 Armenian manuscripts.[7][1] Armenian Weekly writer Levon Saryan noted that the manuscript collection of San Lazzaro consists of over 3,000 complete volumes and about 2,000 fragments.[59] San Lazzaro is usually ranked as the third largest collection of Armenian manuscripts in the world after the Matenadaran in Yerevan, Armenia and the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem.[57][d] The manuscript collection is kept in the rotunda-shaped tower, called the Manuscript Room (manuscript repository). Its construction was funded by Cairo-based Armenian antiques dealer Boghos Ispenian and was designed by his son Andon Ispenian. It was inaugurated in 1970 in attendance of Catholicos Vasken I.[7] [6]

The earliest manuscripts preserved at the repository date to the eighth century.[61][62] Among its notable manuscripts are the 9th century Gospel of Queen Mlke,[63] the early 11th century Adrianopolis Gospel; the Life of Alexander the Great, an Armenian translation of a 5th-century Greek version by Pseudo-Callistene; the Gospels of Gladzor (dated 1307). In 1976–79 some 300 manuscripts were donated by Harutiun Kurdian, for which new display cases were added.[7] It holds one of the ten[64] extant copies of Urbatagirk, the first-ever Armenian book printed by Hakob Meghapart in Venice in 1512.[65] Furthermore, 44 Armenian prayer scrolls (hmayil) are preserved at the repository.[66]

Armenian museum

[edit]

The Armenian museum was designed by Venetian architect Giovanni Rossi and completed in 1867. Seriously damaged by a 1975 fire, it was restored in its present from by Manouk Manoukian. It formerly served as the library of Armenian manuscripts and publications. The museum now houses items related to Armenian history and art, inducing helmets and bronze belts from the Urartian period; the sword of Leo V, the last Armenian King of Cilicia, forged in Sis in 1366;[10] Armenian ceramics from Kütahya; coins, stamps and a passport issued by the 1918–20 First Republic of Armenia. Numerous Armenian religious objects of art from the 16th to 18th centuries are on display. A bas-relief in agate from the medieval Armenian capital of Ani and a curtain formerly hang at the monastery of Lim Island on Lake Van are also on display, along with several paintings by Russian-Armenian marine artist Ivan Aivazovsky, including depictions of Mount Ararat and Niagara Falls. His Biblical creation-themed painting Chaos (1841) was donated to the congregation by Pope Leo XIII in 1901. The death mask of Komitas, the musicologist who established the Armenian national school of music, is also on display in the museum.[7] Also on display is one of the most ancient swords ever found, originating from Anatolia and dating to the 3rd millennium BC.[67][68]

Oriental museum

[edit]

Oriental and Egyptian publications and artifacts are held in what is called the "Lord Byron Room", because it is where he studied Armenian language and culture during his visit to San Lazzaro. It was originally the manuscript room.[7] Its most notable item is the Egyptian mummy, sent to San Lazzaro in 1825 by Boghos Bey Yusufian, an Egyptian minister of Armenian origin. It is attributed to Namenkhet Amun, a priest at the Amon Temple in Karnak, and has been radiocarbon dated to 450–430 BC (late period of ancient Egypt),[69] following the international scientific mission led by Christian Tutundjian de Vartavan to study the mummy, as reported in 1995.[70][71] The mission validated Herodotus' claim that cedar sawdust was used by Ancient Egyptians for embalming, as it fills the stomach of the priest.[72]

The collection also includes Etruscan vases, Chinese antiques,[73] a princely Indian throne with ivory inlay work, and a rare papyrus in 12 segments in Pali of a Buddhist ritual, with bustrophedic writing in red lacquer on gold leaf brought from Madras by a Russian-Armenian archaeologist, who discovered it in a temple in 1830.[7]

Paintings

[edit]Among the art works on display at the monastery corridors are charcoal drawings by Edgar Chahine, landscapes by Martiros Saryan, Mount Ararat by Gevorg Bashinjaghian, a marine painting by Charles Garabed Atamian and a collage by Sergei Parajanov, a triptych by Francesco Zugno depicting the baptism of King Tiridates III by Gregory the Illuminator, various paintings by Luigi Querena, Binding of Isaac by Francesco Hayez, and others.[7]

Publishing house

[edit]A publishing house was established at the island in 1789.[74][7] It was closed down in 1991, however, the Mekhitarists of San Lazzaro continue publication through their publishing house, Casa Editrice Armena.[5][74][75] Until the early 20th century, a number of important publications were made on the island. Khachig Tölölyan wrote of the role the Mekhitarists and their publications:[76]

With astonishing foresight and energy, the scholar-monks of this diasporic enclave set out to accomplish what [Armenian scholar Marc Nichanian] has described as a totalizing project, a cultural program of research and publication that imagined Armenian life and culture as lamentably fragmented, and launched an effort to equip both the deprived homeland population and the artisans and merchants of the diaspora with the wherewithal of a national culture on the European model.

The publications of the Mekhitarists, both in San Lazzaro and Vienna, contributed greatly to the refinement of literary Western Armenian.[77] The San Lazzaro branch became particularly noted in the fields of history, the arts, and literature influenced by the Italian penchant for the arts.[78] The publishing house printed books in dozens of languages, which included themes such as theology, history, linguistics, literature, natural sciences, and economics. They also published textbooks and translations from European languages and editions of classics.[76]

Significant publications

[edit]Among its publications, the most significant work is the two-volume dictionary of Classical Armenian: Բառգիրք Հայկազեան Լեզուի Baṛgirkʻ haykazean lezui (Dictionary of the Armenian Language, 1749–69), which made Armenian the sixth language (after Latin, Greek, French, Italian, and Spanish) to have such a complete dictionary.[79] Its expanded and improved edition, Նոր Բառգիրք Հայկազեան Լեզուի, Nor baṛgirkʻ haykazean lezui (New Dictionary of the Armenian Language, 1836–37), is considered a monumental achievement and remains unsurpassed.[80][81][74] Patrick Considine described the Nor baṛgirkʻ as the "only really useful dictionary" for work on the vocabulary of Classical Armenian (with the exception of Hrachia Acharian's etymological dictionary). He called it a "remarkable work of scholarship in its day and although as a tool of etymological research nearly a hundred and fifty years later it has obvious disadvantages, we should still be lost without it."[82]

Mikayel Chamchian published the first modern history of Armenia in three volumes (1781–86).[83] Ronald Grigor Suny argues that these publications laid the foundations for the emergence of secular Armenian nationalism.[84] Beginning in 1800 a periodical journal has been published at the island. Bazmavep, a literary, historical and scientific journal, was established in 1843 and continues to be published to this day.[85][74]

Role in Armenian history

[edit]An Armenian island in the foreign waters,

You rekindle the old light of Armenia ...

Outside the homeland, for the sake of the homeland.

San Lazzaro has a great historical significance to Armenians and has been described as a "little Armenia."[87][88][89] It is one of the richest Armenian enclaves,[90] and one of the best-known Armenian sites in the world, along with Jerusalem's Armenian Quarter.[91]

Robert Gordon Latham wrote in 1859 that San Lazzaro is the most important Armenian settlement outside Armenia and "the centre of the Armenian literature."[92] William Dean Howells noted in 1866 that "As a seat of learning, San Lazzaro is famed throughout the Armenian world."[93] The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church calls the convent of San Lazzaro and the order of the Mechitarists "especially remarkable" of the religious orders based in Venice.[94] American Protestant missionary Eli Smith noted in 1833 that the convent of San Lazzaro not only did not pursue the "denationalizing system of many of the Romish missions among the oriental churches," but also has done "more than all other Armenians together, to cultivate and enrich the literature of the nation."[95] Louisa Stuart Costello called the Armenian convent of San Lazzaro "a respectable pile, above the encircling waters, an enduring monument of successful perseverance in a good cause."[96]

Cultural awakening

[edit]According to Robert H. Hewsen for nearly a century—until the establishment of the Lazarev Institute in Moscow in 1815—the monastery of San Lazzaro was the only center of intensive Armenian cultural activity that held the heritage of the Armenian people.[97] During the 18th century, the rediscovery of classical Armenian literature and the creation of an Armenian vernacular by the Mechitarists of San Lazzaro was a key factor in the "Armenian Renaissance."[98] Italian scholar Matteo Miele compared the work of the Mekhitarists carried out in the island to the work of the humanists, painters and sculptors of the Italian Renaissance.[99] For over a century the monastery of San Lazzaro became the "potent agency for the advancement of secular, as well as of religious, knowledge" with "avowed religious, educational, and literary objectives like those of the medieval Benedictine order."[100]

- National consciousness and nationalism

The activities of the island monastery, which became a center for Armenian studies, led to a revival of Armenian national consciousness.[101] According to Harry Jewell Sarkiss the emphasis Mekhitarists of San Lazzaro put on "their national history and language was significant, for thereby they planted the seeds" of modern Armenian nationalism.[100] Elizabeth Redgate writes that the developments in intellectual culture and scholarship in Russian Armenia and at the Mkhitarist monasteries of San Lazzaro and Vienna inspired an increased nationalism among Armenians in the 1880s.[102] Mary Tarzian suggests that nationalism among Armenians in the Ottoman Empire emerged from the educational vision of the Mechitarists in San Lazzaro.[103] This view was expressed as early as 1877 when Charles Yriarte wrote that the Armenians "look with justice upon the island of San Lazzaro as the torch which shall one day illuminate Armenia, when the hour comes for her to live again in history and to take her place once more among free nations."[104]

However, their activities were not without criticism. Mikael Nalbandian, a liberal and anti-clerical Russian-Armenian writer, wrote in the mid-19th century that the "enlightenment of our nation must proceed from the hands of execrable papist monks! Their 'light' is far more pernicious than darkness."[105]

Notable resident scholars

[edit] Mkhitar Sebastatsi (1676–1749) |

The founder of the Mkhitarist (Mechitarist) Order. He resided in the island from the time of the settlement of his congregation in 1717 until his death. He set the foundations of modern philological studies of the Armenian language by publishing books on grammar and dictionaries.[106] He published some 20 works, mostly on the subjects of theology and philosophy, including an Armenian edition of the Bible (1733), a commentary on the Gospel of Matthew (1737), Armenian grammar, dictionary, and catechism.[107] | |

Mikayel Chamchian (1738–1823) |

A historian who lived in the island from 1757 until his death.[108] He authored the first modern history of Armenia, in three volumes (1781–86).[83] It is a comprehensive and influential publication which was used as a reference work by scholars for over a century. According to Hacikyan et al. it is a "great achievement in Armenian historiography judging by the criteria of his own time."[109] | |

Gabriel Aivazovsky (1812–1880) |

A philologist, historian and publisher, whose younger brother, Ivan (Hovhannes) Aivazovsky, was a famed Russian seascape artist. He studied at the island school from 1826 to 1830 and was later the secretary of the Mekhitarian congregation. He founded and edited the San Lazzaro-based journal Bazmavep from 1843 to 1848.[110] | |

Ghevont Alishan (1820–1901) |

A prominent historian, was a member of the Mechitarist Order since 1838. In 1849–51 he edited the journal Bazmavep and taught at the monastic seminary in 1866–72.[111] He lived in the island permanently from 1872 until his death in 1901.[112] He authored books on the history and geography of Armenians regions of Shirak, Ayrarat, Sisakan (all published in 1881–83) with "amazing accuracy." In 1895 he published two notable works, one on pre-Christian polytheistic religion of Armenians and a study on 3,400 species of plants that grow in Armenia.[113] |

Notable students

[edit]- Gabriel Aivazovsky, Armenian archbishop[114]

- Tserents, Armenian writer[115]

- Hrant Maloyan, Syrian commander[116]

- Alicia Terzian, Argentine musicologist[117]

Notable visitors

[edit]A wide range of notable individuals have visited the island through centuries.

Lord Byron

[edit]

English Romantic poet Lord Byron visited the island from November 1816 to February 1817.[119][5] He acquired enough Armenian to translate passages from Classical Armenian into English.[120] He co-authored English Grammar and Armenian in 1817, and Armenian Grammar and English in 1819, where he included quotations from classical and modern Armenian.[121] The room where Byron studied now bears his name and is cherished by the monks.[45][122] There is also a plaque commemorating Byron's stay.[46][123] Byron is considered the most prominent of all visitors of the island.[5][124][122] James Morris wrote in 1960 that "many people in Venice, asked to think of San Lazzaro, think first of Byron, and only secondly of the Armenians. Byron's spirit haunts the island."[16]

Non-Armenians

[edit]Pope Pius VII visited the island on May 9, 1800.[31] Since the 19th century numerous notable individuals visited San Lazzaro, such as composers Jacques Offenbach,[125] Gioachino Rossini,[125] Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky,[126] and Richard Wagner (1859),[127] writers Alfred de Musset and George Sand (1834),[128][129][130] Marcel Proust (1900),[131] Ivan Turgenev,[126] Nikolai Gogol,[126] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,[5] British art critic John Ruskin (early 1850s),[132] and French historian Ernest Renan (1850).[125]

During the 19th century numerous monarchs visited the island, including Charles IV of Spain, Franz Joseph I of Austria, Umberto I of Italy, Charles I of Romania, Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, Wilhelmina of the Netherlands,[125] Prince Napoléon Bonaparte,[133] Ludwig I of Bavaria, (1841),[134] Margherita of Savoy,[135] Maximilian I of Mexico,[135] Carlota of Mexico,[135] Edward VII, Prince of Wales and future British king (1861),[135] Napoleon III (1862),[135] Pedro II of Brazil (1871),[135] Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1881),[135] Alexander I of Russia.[125] U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and British Prime Minister William Gladstone visited San Lazzaro in 1878 and 1879, respectively.[136][137]

An undocumented account claims that Joseph Stalin, a Bolshevik revolutionary at the time, worked as a bell-ringer at the monastery in 1907.[138][139]

Armenians

[edit]The marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky visited San Lazzaro in 1840. He met his older brother, Gabriel, who was working at the monastery at that time. At the monastery library and the art gallery Aivazovsky familiarized himself with Armenian manuscripts and Armenian art in general.[140] Another Armenian painter, Vardges Sureniants, visited San Lazzaro in 1881 and researched Armenian miniatures.[141] Ethnographer Yervand Lalayan worked at the island for around six months in 1894.[142] Musicologist Komitas lectured on Armenian folk and sacred music and researched the Armenian music notation (khaz) system in the monastery library in July 1907.[90] The first meeting of poets Yeghishe Charents and Avetik Isahakyan took place in San Lazzaro in 1924.[143] Composer Aram Khachaturian visited it in 1963,[144] and astrophysicist Viktor Ambartsumian in 1969.[145]

At least two catholicoi (leaders) of the Armenian Apostolic Church—which was historically a rival of the Armenian Catholic Church, which the Mekhitarists are a part of[122]—have visited the island. Vazgen I visited twice, in 1958 and 1970,[146][147] and Karekin II visited in 2008.[148]

Since independence in 1991 at least three presidents of Armenia—Robert Kocharyan in 2005, Serzh Sargsyan in 2011, and Armen Sarkissian (with his wife Nouneh Sarkissian) in 2019—visited San Lazzaro.[149][150][151] Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan visited in 2019.[152]

Henrikh Mkhitaryan, the most prominent Armenian football player, married Betty Vardanyan at the monastery of San Lazzaro on June 17, 2019.[153][154]

Artistic depictions

[edit]Numerous artists have painted the island, including

- Vignette of the Isola di S. Lazzaro degli Armeni by Antonio Visentini (d. 1782, undated), Royal Collection, Windsor Castle[155]

- Island of Surb Ghazar at night by Gevorg Bashinjaghian (1892), National Gallery of Armenia[156]

- Byron's visit to the Mekhitarists in Surb Ghazar Island by Ivan Aivazovsky (1899), National Gallery of Armenia[118]

- The Armenian Convent by Joseph Pennell (1905), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division[157]

- Sb. Ghazar island, Venice by Hovhannes Zardaryan (1958), National Gallery of Armenia[158]

See also

[edit]- Mekhitarist Monastery, Vienna

- Armenians in Italy

- List of Armenian ethnic enclaves

- Santa Croce degli Armeni

- Armenian Catholic Church

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ also romanized as Sourb, S(o)urp, andŁazar.

- ^ Western Armenian pronunciation of վարդանուշ, vardanush literally translating to "sweet rose"; also a female given name.

- ^ Variously given as 150,000,[5][53][6][54] 170,000,[7] 200,000.[10][55]

- ^ Matenadaran holds 11,000 Armenian manuscripts in the strict sense[57] and 17,000 in total.[60] The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem has 3,890 inventoried manuscripts.[57]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Levonian Cole, Teresa (25 September 2015b). "The monk keeping his Armenian heritage alive in Venice". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022.

- ^ "In Historic Move Venice and Vienna Mekhitarist Orders Unite". Asbarez. 24 July 2000. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ a b c "San Lazzaro degli Armeni". turismovenezia.it (in Italian). Provincia di Venezia. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Adalian 2010, p. 426-427.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gordan, Lucy (February 2012). "The Venetian Island of St. Lazarus: Where Armenian Culture Survived the Diaspora". Inside the Vatican: 38–40. web version (archived)

- ^ a b c d Luther, Helmut (12 June 2011). "Venedigs Klosterinsel [Venice's monastic island]". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 2 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad "The Island of San Lazzaro". mechitar.com. Armenian Mekhitarist Congregation. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015.

- ^ Belford, Ros; Dunford, Martin; Woolfrey, Celia (2003). Italy. Rough Guides. p. 332.

- ^ Avagyan, Lilit (26 August 2007). "Ազգինը՝ ազգին, Հռոմինը՝ Հռոմին [The national to the nation, the Roman to Rome]". 168.am (168 Hours Online) (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

Կղզի ամեն տարի այցելում է մոտ 40.000 զբոսաշրջիկ: = Around 40,000 tourists visit the island annually.

- ^ a b c d Levonian Cole, Teresa (31 July 2015). "San Lazzaro degli Armeni: A slice of Armenia in Venice". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017.

- ^ Valcanover, Francesco (1965). "Collection of the Armenian Mekhitarist Fathers, Island of St. Lazarus of the Armenians". Museums and Galleries of Venice. Milan: Moneta Editore. p. 149.

- ^ "Island of Saint Lazarus of the Armenians". Michelin Guide. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Greenwood, Tim (2012). "Armenia". In Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-533693-1.

- ^ a b Langlois 1874, p. 13.

- ^ a b Russell 1842, p. 372.

- ^ a b c Morris 1960, p. 294.

- ^ Toth, Susan Allen (19 April 1998). "Hidden Venice". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ a b Langlois 1874, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Nurikhan 1915, p. 231.

- ^ a b Langlois 1874, p. 20.

- ^ Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Nurikhan 1915, p. 236.

- ^ a b "Սուրբ Ղազար [Surb Ghazar]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 11 (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing House. 1985. pp. 203–204.

- ^ Nurikhan 1915, p. 237.

- ^ Langlois 1874, p. 23.

- ^ Langlois 1874, p. 24.

- ^ Yriarte 1880, p. 302.

- ^ Flagg, Edmund (1853). Venice: The City of the Sea: From the Invasion by Napoleon in 1797 to the Capitulation to Radetzky in 1849, Volume I. New York: Charles Scribner. p. 263.

As for convents and monasteries, he suppressed all—that of the Armenians only excepted.

- ^ a b Russel, C. (19 February 1870). "Armenia and the Armenians". The Church of England Magazine. LXVIII: 107.

- ^ Buckley, Jonathan (2010). The Rough Guide to Venice & the Veneto (8th ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-84836-870-5.

- ^ a b "From the Fall of the Venetian Republic to the Napoleonic Decree Recognizing the Congregation". mechitar.com. Armenian Mekhitarist Congregation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Le comunita' religiose nelle isole (Religious communities in the islands)". turismo.provincia.venezia.it (in Italian). Città metropolitana di Venezia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

Pur trattandosi di una comunità religiosa, questa non venne soppressa da Napoleone che la considerò un'accademia letteraria probabilmente in rapporto all'importante attività editoriale svolta dai monaci.

- ^ "Monastère mékhitariste de Saint-Lazare <Venise, Italie> (1717 - )". cerl.org. Consortium of European Research Libraries. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022.

- ^ Editorial (1967). "Ողողում Սուրբ Ղազար վանքում". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 23 (1–2). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. Archived from the original on 2019-09-21. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- ^ McGarry, Kevin (12 May 2015). "Highlights From the 56th Venice Biennale". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Republic of Armenia Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale". artsy.net. 18 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Golden Lions for Armenia, Adrian Piper at Venice Biennale". Deutsche Welle. 10 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Հեղեղվել է Վենետիկի սուրբ Ղազար կղզին" (in Armenian). News on First Channel. 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Վենետիկի Սուրբ Ղազար կղզին ջրհեղեղի պատճառով վնասներ է կրել". factor.am (in Armenian). 14 November 2019. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019.

- ^ Kechichian, Hamazasp (November 13, 2019). "Ս. Ղազար կղզին ալ զերծ չմնաց բնութեան այս աղէտէն" (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Monastero Mechitarista". turismovenezia.it (in Italian). Provincia di Venezia. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Memorial on Saint Lazarus Island, Venice, Italy". Armenian National Institute. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2015-01-25.

- ^ Clement, Clara Erskine (1893). The Queen of the Adriatic or Venice, Mediaeval and Modern. Boston: Estes and Lauriat. p. 312.

- ^ Macfarlane, Charles (1830). The Armenians: A Tale of Constantinople, Volume 1. Philadelphia: Carey and Lea. p. 254.

San Lazaro is about the middle size, and adorned with a pretty garden ...

- ^ a b Garrett, Martin (2001). Venice: A Cultural and Literary Companion. New York: Interlink Books. p. 166.

- ^ a b Carswell, John (2001). Kahn, Robert (ed.). Florence, Venice & the Towns of Italy. New York Review of Books. p. 143.

- ^ Robertson, Alexander (1905). The Roman Catholic Church in Italy. Morgan and Scott. p. 186.

- ^ Blake, Edith Osborne (1876). Twelve Months in Southern Europe. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 144.

- ^ "Maggio: le rose". la Repubblica (in Italian). 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

Mentre di origine armena è la "vartanush", la marmellata di rose che in Italia viene prodotta a Venezia, nell'Isola di San Lazzaro degli Armeni dai monaci Mechitaristi.

- ^ "Isola di San Lazzaro degli Armeni" (in Italian). Italian Botanical Heritage. Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

Una tecnica secolare ne imprigiona i profumi nella Vartanush, la marmellata di petali di rose che, tradizionalmente, vengono colti al sorgere del sole.

- ^ Davies, Emiko (10 May 2011). "Rose petal Jam from a Venetian monastery". emikodavies.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Gora, Sasha (8 March 2013). "San Lazzaro degli Armeni – Where Monks Make Rose Petal Jam in Venice, Italy". Honest Cooking. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Saryan 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Mayes, Frances (23 December 2015). "The Enduring Mystique of the Venetian Lagoon". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

What the monastery is most known for is the library of glass-fronted cases holding some of the monks' 150,000 volumes ...

- ^ Dunglas, Dominique (20 April 2011). "La possibilité des îles [The possibility of islands]". Le Point (in French). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

San Lazzaro degli Armeni. La bibliothèque du monastère, où vivent une poignée de moines arméniens, ne compte pas moins de 200 000 livres précieux ...

- ^ "Aurora Honors the Memory of Vartan Gregorian with a $50,000 Grant to the Library of the Mekhitarist Congregation at San Lazzaro". auroraprize.com. 28 October 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Coulie 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Coulie 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Saryan 2011, p. 3.

- ^ "Mesrop Mashtots Matenadaran". armenianheritage.org. Armenian Monuments Awareness Project. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Mesrobian 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Fodor's Venice & the Venetian Arc. Fodor's Travel Publications. 2006. p. 68.

- ^ Kouymjian, Dickran. "Index of Armenian Art: Queen Mlk'e Gospel". armenianstudies.csufresno.edu. California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original on 2010-06-13.

- ^ Trvnats, Anush (28 April 2012). "Թուեր Եւ Փաստեր' Հայ Գրատպութեան Պատմութիւնից [Number and facts from the history of Armenian printing]". Aztag (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

«Ուրբաթագրքի» առաջին հրատարակութիւնից աշխարհում պահպանուել է 10 օրինակ

- ^ Yapoudjian, Hagop (14 October 2013). "Մտորումներ Սուրբ Ղազար Այցելութեան Մը Առիթով [Thoughts on visit to San Lazzaro]". Aztag (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Ghazaryan, Davit (2014). "Կիպրիանոս հայրապետը և Հուստիանե կույսը 15-16-րդ դարերի ժապավենաձև հմայիլների գեղարվեստական հարդարանքում [Patriarch Kyprianos and Justinia the virgin in the artistic decoration of 15th-16th century ribbon-like hmayils]" (PDF). Banber Matenadarani (in Armenian): 244. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 27, 2015.

- ^ Giuliani-Hoffman, Francesca (26 March 2020). "5,000-year-old sword is discovered by an archaeology student at a Venetian monastery". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ Metcalfe, Tom (March 11, 2020). "Student discovers 5,000-year-old sword hidden in Venetian monastery". Live Science. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ Huchet, Jean-Bernard (2010). "Archaeoentomological study of the insect remains found within the mummy of Namenkhet Amun (San Lazzaro Armenian Monastery, Venice/Italy)". Advances in Egyptology (1): 59–80.

- ^ "Envoyé Spécial - La momie et ses secrets". mif-sciences.net (in French). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023.

- ^ Grenier, Jean-Claude (October 1995). "La science au chevet des momies". Géo Magazine (200). Archived from the original on 2023-10-29. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Amorós, Victoria Asensi; Vozenin-Serra, Colette (1998). "New Evidence for the Use of Cedar Sawdust for Embalming by Ancient Egyptians". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 84: 228–231. doi:10.2307/3822223. JSTOR 3822223. Archived from the original on 2023-11-02. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ "Venise insolite: La flamme arménienne au cœur de la lagune [Unusual Venice: Armenian flame at the heart of the lagoon]" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Mouradyan, Anahit (2012). "Հայ տպագրության 500-ամյակը [The 500th Anniversary of the Armenian Book-Printing]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 1 (1): 58–59. Archived from the original on 2015-01-22. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ "Президент Армении принял аббата братства мхитаристов [President of Armenia received abbot of Mekhitarist brotherhood]" (in Russian). REGNUM News Agency. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

Типография ордена, где кстати печатались книги на 36 языках, была закрыта в 1991 году.

- ^ a b Tölölyan, Khachig (2005). "Armenian Diaspora". In Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.). Encyclopedia of Diasporas. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

- ^ Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Suny 1993, p. 56.

- ^ Suny 1993, p. 251.

- ^ Mathews, Edward G. Jr. (2000). "Armenia". In Johnston, Will M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L. Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 86–87.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the monastery in Venice produced hundreds of editions of Armenian texts, a number of important studies, and a dictionary of classical Armenian that is still unsurpassed.

- ^ Considine, Patrick (1979). "Semantic Approach to the Identification of Iranian Loanwords in Armenian". In Brogyanyi, Bela (ed.). Studies in Diachronic, Synchronic, and Typological Linguistics: Festschrift for Oswald Szemerényi on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday, Part 1. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 215, 225 (footnote 5). ISBN 978-90-272-3504-6.

- ^ a b Suny 1993, pp. 57, 252.

- ^ Suny 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Conway Morris, Roderick (24 February 2012). "The Key to Armenia's Survival". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Օտար ջրերում հայացեալ Կղզի / Հայոց հին լույսն է քեզնով նորանում ... / Հայրենիքից դուրս՝ հայրենեաց համար: "Հայերն Իտալիայում [Armenians in Italy]". italy.mfa.am (in Armenian). Embassy of Armenia to Italy. Archived from the original on 2015-01-18. Retrieved 2015-01-18.

- ^ "Armenia Wins Venice Biennale 2015 Golden Lion Award". Armenian Weekly. 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, said during his 2008 to the island that San Lazzaro is "a little Armenia thousands of kilometers away from Armenia." "Ն.Ս.Օ.Տ.Տ. Գարեգին Բ Ամենայն Հայոց Կաթողիկոսի խոսքը Մխիթարյան միաբանությանը Սուրբ Ղազար կղզում [Visit of Catholicos Karekin II to the Mekhitarist Congregation at San Lazzaro island]" (PDF). Etchmiadzin (in Armenian) (5): 28. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2015.

Սուրբ Ղազարը Հայաստանից հազարավոր կիլոմետրեր հեռու մի փոքր Հայաստան է

- ^ "Armenians Desirous of a United Country". The New York Times. 6 March 1919. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

The island of San Lazzaro, near Venice, has been for over two centuries an Armenian oasis transplanted in the Venetian lagoons.

- ^ a b Soulahian Kuyumjian, Rita (2001). Archeology of Madness: Komitas, Portrait of an Armenian Icon. Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-903656-10-5.

- ^ Bakalian, Anny (1993). Armenian Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-1-56000-025-9.

- ^ Latham, R. G. (1983) [1859]. Tribes and Races: A Descriptive Ethnology Of Asia, Africa And Europe Vol 2. Delhi: Cultural Publishing House. pp. 70-73.

- ^ Howells, William Dean (1907) [1866]. Venetian Life. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 180.

- ^ Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds. (2005) [1957]. "Venice". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1699. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

Of the many religious orders that have houses in Venice the Armenian Benedictine Congregation of the Mechitarists is esp. remarkable; their convent on the island of San Lazzaro is a centre of Armenian education.

- ^ Smith, Eli (1833). Researches of the Rev. E. Smith and Rev. H.G.O. Dwight in Armenia: Including a Journey Through Asia Minor, and Into Georgia and Persia, with a Visit to the Nestorian and Chaldean Christians of Oormiah and Salmas, Volume 1. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. pp. 256–257.

- ^ Costello, Louisa Stuart (1846). A Tour to and from Venice, by the Vaudois and the Tyrol. London: John Ollivier. p. 317.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 12, 158. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Sarkiss 1937, p. 441.

- ^ Miele, Matteo (16 October 2015). "L'isola degli Armeni a Venezia". Il Post (in Italian). Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

Lontani, quasi appartati, hanno prodotto, per il proprio popolo, una rinascita artistica, letteraria e sociale in qualche modo paragonabile all'opera dei grandi umanisti, pittori e scultori del Rinascimento italiano.

- ^ a b Sarkiss 1937, p. 443.

- ^ Dursteler, Eric R. (2013). A Companion to Venetian History, 1400–1797. Brill Publishers. p. 459. ISBN 978-90-04-25251-6.

... the island of San Lazzaro on which he established a monastery that became a center for Armenian studies and led to a revival of Armenian consciousness.

- ^ Redgate, A. E. (2000). The Armenians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-631-22037-4.

- ^ Terzian, Shelley (2014). "Central effects of religious education in Armenia from Ancient Times to Post-Soviet Armenia". In Wolhuter, Charl; de Wet, Corene (eds.). International Comparative Perspectives on Religion and Education. SUN MeDIA. p. 37.

- ^ Yriarte 1880, p. 302.

- ^ Suny 1993, p. 61.

- ^ Adalian 2010, p. xlv.

- ^ El-Hayek, E. (2003). "Mechitar". New Catholic Encyclopedia (9th ed.). Thomson/Gale. p. 421. ISBN 9780787640040. Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ Utudjian, A. A. (1988). "Միքայել Չամչյան (կյանքի և գործունեության համառոտ ուրվագիծ) [Michael Chamchian (a short description of his life and activity)]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri. 9 (9): 71–85. Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ^ Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Mikayelyan, V. (2002). "Այվազովսկի Գաբրիել [Aivazovsky Gabriel]" (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies. Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ Asmarian, H. A. (2003). "Ղևոնդ Ալիշանի ճանապարհորդական նոթերից [From Ghevond Alishan's travel notes]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). 2 (2): 127–135. Archived from the original on 2015-01-22. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ Shtikian, S. A. (1970). "Ղևոնդ Ալիշան [Ghevond Alishan]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 2 (2): 13–26. Archived from the original on 2015-01-22. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ^ Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 54.

- ^ "Այվազովսկի Գաբրիել [Ayvazvovsky Gabriel]". armenianreligion-am.arm (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute of Armenian Studies. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Ծերենց (Տոքթ. Յովսէփ Շիշմանեան, 1822-1888). Հայ Ժողովուրդի Ազատագրական Պայքարի Պատմութեան Վիպագիրը". Aztag (in Armenian). October 3, 2015. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ "ՄՈՒՇԷՆ – ԴԱՄԱՍԿՈՍ ՀԱՅՐԵՆԱՍԷՐ ՊԷԿԸ՝ ԶՕՐ. ՀՐԱՆԴ ՄԱԼՈՅԵԱՆ". kantsasar.com (in Armenian). June 3, 2022. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Alicia Terzian". Komitas Museum. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Բայրոնի այցը Մխիթարյաններին Սբ. Ղազար կղզում (1899)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- ^ Mesrobian 1973, p. 27.

- ^ Mesrobian 1973, p. 31.

- ^ Elze, Karl (1872). Lord Byron, a biography, with a critical essay on his place in literature. London: J. Murray. pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b c Saryan 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Vangelista, Massimo (4 September 2013). "Lord Byron in the Armenian Monastery in Venice". byronico.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Seferian, Nareg (21 March 2017). "The Armenian Island of Venice". Euronews. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Deolen, A. (1919). "The Mekhitarists". The New Armenia. 11 (7): 104.

- ^ a b c Kolupaev, Vladimir (2011). "Монастырь на острове Сан-Ладзаро [Monastery of the island of San Lazzaro]". Vostochnaya Kollektsiya (in Russian) (2): 43–51. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019.

- ^ Barker, John W. (2008). Wagner and Venice. University of Rochester Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-58046-288-4.

- ^ de Musset, Alfred (1867). Oeuvres, Volume 7 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. p. 246.

Après le repas, ils montaient en gondole, et s'en allaient voguer autour de l'île des Arméniens ...

- ^ Winegarten, Renee (1978). The double life of George Sand, woman and writer: a critical biography. Basic Books. p. 134. ISBN 9780465016839.

- ^ Sand, George (1844). "Venise, juillet 1834.". Œuvres de George Sand: Un hiver au midi de l'Europe (in French). Paris: Perrotin. p. 95.

Nous arrivâmes à l'île de Saint-Lazare, où nous avions une visite à faire aux moines arméniens.

- ^ Plant, Margaret (2002). Venice: fragile city 1797–1977. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-300-08386-6.

- ^ Cook, Edward Tyas (1912). Homes and Haunts of John Ruskin. New York: Macmillan. pp. 111–112.

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward (1868). From the Oak to the Olive: A Plain Record of a Pleasant Journey. Library of Alexandria. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-4655-1372-4.

- ^ Das Armenische Kloster auf der Insel S. Lazzaro bei Venedig (in German). Armenische Druckerei. 1864.

- ^ a b c d e f g Issaverdenz 1890, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Grant, Julia Dent (1988). Simon, John Y. (ed.). The personal memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant). Southern Illinois University Press. p. 243. ISBN 9780809314423.

- ^ Lucas, Edward Verrall (1914). A Wanderer in Venice. The Macmillan Company. p. 302.

- ^ "When Stalin in Venice ..." (PDF). Venice Magazine. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-07-13.

Josif Stalin, the Russian dictator, was one of the last bell-ringers of the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, located at the heart of the lagoon. He stowed away in the port of Odessa to escape from tsarist police and arrived in Venice in 1907.

- ^ Salinari, Raffaele K. (2010). Stalin in Italia ovvero "Bepi del giasso" (in Italian). Bologna: Ogni uomo è tutti gli uomini Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-96691-01-4. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

Qui forse trovò alloggio nel convento adiacente alla chiesa di San Lazzaro degli Armeni, sita su un'isoletta al largo della città.

- ^ Khachatrian, Shahen. ""Поэт моря" ["The Sea Poet"]" (in Russian). Center of Spiritual Culture, Leading and National Research Samara State Aerospace University. Archived from the original on 2014-03-19. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ^ Adamyan, A. (2012), Վարդգես Սուրենյանց [Vardges Sureniants] (PDF) (in Armenian), National Library of Armenia, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04

- ^ Melik-Pashayan, K. (1978). "Լալայան Երվանդ [Lalayan Yervand]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 4 (in Armenian). p. 475.

- ^ "Իսահակյանի և Չարենցի առաջին հանդիպումը Վենետիկում [First meeting of Isahakyan and Charents in Venice]". magaghat.am (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

Մեծատաղանդ բանաստեղծ Եղիշե Չարենցին առաջին անգամ տեսա Վենետիկում, 1924 թվականին: ... Գնում էինք ծովափ, հետո գնում էինք Մխիթարյանների վանքը` Սուրբ Ղազար:

- ^ "Ֆոտոալբոմ [Photo gallery]". akhic.am (in Armenian). Aram Khachaturian International Competition. Archived from the original on 2014-09-13.

Ա.Խաչատրյանը Մխիթարյան միաբանությունում Սուրբ Ղազար կղզի 1963

- ^ Rosino, Leonida [in Italian] (1988). "Encounters with Victor Ambartsumian one afternoon at the San Lazzaro Degli Armeni island at Venice". Astrophysics. 29 (1): 412–414. Bibcode:1988Ap.....29..412R. doi:10.1007/BF01005854. S2CID 120007462.

- ^ Editorial (1958). "Վեհափառ Վազգեն Ա Կաթողիկոսի այցը Սուրբ Ղազար". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 15 (7): 45. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19.

- ^ Editorial (1970). "Ամենայն Հայոց Վեհափառ Հայրապետի իններորդ ուղևորությունը արտասահման". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 27 (8): 12–52. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19.

- ^ "Catholicos Concludes Vatican Visit". Asbarez. 13 May 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ ՀՀ նախագահ Ռոբերտ Քոչարյանը պաշտոնական այցով կմեկնի Իտալիա [President of Armenia Robert Kocharyan will visit Italy] (in Armenian). Armenpress. 25 January 2005. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "President Serzh Sargsyan visited the Mkhitarian Congregation at the St. Lazarus Island in Venice". president.am. Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia. 14 December 2011. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Armenian President and First Lady visit Mekhitarist monks in San Lazzaro, Italy". Armenpress. 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Nikol Pashinyan's official visit to Italy kicks off; PM visits Mekhitarist Congregation". primeminister.am. The Office to the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia. 20 November 2019. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Mkhitaryan Ties the Knot". Asbarez. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ ""Marry me and stay with me forever": Henrikh Mkhitaryan marries fiancée Betty Vardanyan". mediamax.am. 18 June 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Vignette of the Isola di S. Lazzaro degli Armeni". Royal Collection. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Սբ. Ղազար կղզին գիշերով (1892)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- ^ Pennell, Joseph (1905). "The Armenian convent". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2018-03-29. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

- ^ "Սբ Ղազարի կղզին. Վենետիկ (1958)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

Bibliography

[edit]Books on San Lazzaro

[edit]- Peratoner, Alberto (2007; 2015). From Ararat to San Lazzaro. A Cradle of Armenian Spirituality and Culture in the Venice Lagoon. - Contributions by Fr. Vertanes Oulouhodjan and H.E. Boghos Levon Zekiyan. Venice: Congregazione Armena Mechitarista - Casa Editrice Armena.

- Issaverdenz, James (1890). The Island of San Lazzaro, Or, The Armenian Monastery Near Venice. Armenian typography of San Lazzaro.

- Langlois, Victor (1874). The Armenian Monastery of St. Lazarus-Venice. Venice: Typography of St. Lazarus.

Articles on San Lazzaro

[edit]- Russell, C. W. (May 1842). "The Armenian Convent of San Lazzaro, at Venice". The Dublin Review. 12: 362–386.

- Saryan, Levon A. (July–August 2011). "A Visit to San Lazzaro: An Armenian Island in the Heart of Europe". Armenian Weekly. Part I, Part II, Part III

- Shcherbakova, Vera (20 November 2014). "Таинственный "остров армян" [Mysterious "island of Armenians"]". Chastny Korrespondent (in Russian). via euromag.ru.

- "The Armenian Convent in Venice". The New York Times. 7 April 1878.

Other books

[edit]- Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 426–427. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- Coulie, Bernard (2014). "Collections and Catalogues of Armenian Manuscripts". In Calzolari, Valentina (ed.). Armenian Philology in the Modern Era: From Manuscript to Digital Text. Brill Publishers. pp. 23–64. ISBN 978-90-04-25994-2.

- Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2005). "The Mkhitarist (Mekhitarist) Order". The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the eighteenth century to modern times. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 50–55. ISBN 978-0-8143-3221-4.

- Mackay, George Eric (1876). Lord Byron at the Armenian Convent. Venice: Office of the "Poliglotta".

- Morris, James (1960). The World of Venice. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Nurikhan, Minas (1915). The Life and Times of Abbot Mechitar. Rev. John Mc Quillan (translator). Venice: St. Lazarus's Island.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20773-9.

- Yriarte, Charles (1880) [1877]. Venice: Its History, Art, Industries and Modern Life (Venise: l'histoire, l'art, l'industrie, la ville et la vie). Sitwell, F. J. (translator). New York: Scribner and Welford. pp. view=1up, seq=423 301–306.

Other articles

[edit]- Mesrobian, Arpena (1973). "Lord Byron at the Armenian Monastery on San Lazzaro". The Courier. 11 (1): 27–37.

- Sarkiss, Harry Jewell (December 1937). "The Armenian Renaissance, 1500–1863". The Journal of Modern History. 9 (4): 433–448. doi:10.1086/243464. JSTOR 1899203. S2CID 144117873.

Further reading

[edit]- Maguolo, Michela; Bandera, Massimiliano (1999). San Lazzaro degli Armeni: l'isola, il monastero, il restauro (in Italian). Venezia: Marsilio. ISBN 978-88-317-7422-2. OCLC 247889977.

- Bolton, Claire (1982). A visit to San Lazzaro. Oxford, England: Alembic Press. OCLC 46689623.

- Richardson, Nigel (13 February 2011). "Oasis in the bedlam of Venice". The Times. London.

- Horne, Joseph (1872). "St. Lazzaro, Venice, and its Armenian Convent". The Ladies' Repository. 32 (10): 459.

- Pasquin Valery, Antoine Claude [in French] (1839) [1838]. Historical, literary, and artistical travels in Italy, a completer and methodical guide for travellers and artists [Voyage en Italie, guide du voyageur et de l'artiste]. Paris: Baudry. pp. 191–192.

- Fell, Cicely (31 December 2014). "Out of Armenia, Venice". BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014.